THE OTHER SIDE. The opioid crisis that plagues the U.S. goes beyond opioid addiction and drug overdoses. It encompasses the plight of pain patients as the supply of opioids for proper medicinal use dwindles. Attention needs to be given to both sides of the crisis.

‘The other side’

Hospitals, pain patients face shortage of painkillers due to changing guidelines

May 7, 2018

When we hear the words “opioid crisis,” we tend to think about the tragic lives lost to addiction and overdoses.

But there is another opioid crisis that rages on at the same time, one that many do not think about: the inability of pain patients to obtain the medication they need to function.

Hospital Shortages

One reason rests in the supply of opioids in hospitals.

While opioids flood American communities and fuel rampant addiction, hospitals are facing a massive shortage of the painkillers needed by patients with acute pain including morphine, Dilaudid, and fentanyl.

The shortage is due to manufacturing setbacks and the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA)’s call for a 25 percent reduction of all opioid manufacturing last year and an additional 20 percent this year, its effort to reduce addiction.

As a result, hospital pharmacists are struggling to find alternatives as nurses are forced to administer second-choice drugs or deliver standard drugs in other ways.

These actions increase the risk of mistakes, especially since calculating dosages can be difficult. In fact, according to the nonprofit Institute for Safe Medication Practices, there have been a few instances of patients receiving potentially harmful doses.

Such doses “can lead to severe harm or fatalities,” making opioid shortages more risky than the more common shortages of injectable drugs, as Mike Ganio, a medication safety expert at the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, told The Washington Post.

“The system has been set up safely for the drugs and the care processes that we ordinarily use.

“You change those drugs, and you change those care processes, and the safety that we had built in is just not there anymore,” said Dr. Beverly Philip, a Harvard University professor of anesthesiology who practices at Brigham and Women’s Hospital.

Some pain patients are receiving less effective medications as hospitals conserve their limited resources to high-priority cases; meanwhile, others remain in pain because needed medications are unavailable or waiting for oral drugs substituting opioids to take effect.

In a letter to the DEA, various professional medical groups warned that “having diminished supply of these critical drugs, or no supply at all, can cause suboptimal pain control or sedation for patients.”

States’ Maximum Limits

The crisis, however, does not end there.

Long-term pain patients who have relied on opioid analgesics for years are now no longer able to fill their prescriptions in many states due to set maximum dosage and supply limits, ranging from three to 14 days.

Ohio currently has limits of five-day prescriptions for minors with parental consent and seven-day prescriptions for adults, with exceptions of 30 days for morphine equivalent doses (MEDs).

Though exceptions are made for long-term pain care such as for cancer patients, insurance companies and pharmacy policies can now deny coverage or fills based on such laws.

As a result, pain patients are denied treatment and waned off of the opioids they rely on to function even if they have never shown risks of abuse.

“Twenty years ago…the Joint Commission, a healthcare accreditation board, introduced the ‘fifth vital sign,’ which required health-care providers to ask patients whether they had pain and how severe it was as part of the routine assessment of vital signs.

“Now we’ve done an about-face because of opioid abuse to implement policies that will cause physicians to abandon patients or taper medications regardless of whether this will harm their quality of life,” said Anne Fuqua, former nurse and current pain patient, in an article submitted to The Washington Post.

The Ones Affected

“Sometimes you just need to take two Bufferin or something and go to bed,” said Attorney General Jefferson Sessions to the online news magazine The Week, in response to pain patients’ concerns.

His words reveal a clear misunderstanding.

50 million Americans suffer from severe or persistent pain, according to the National Institute of Health (NIH). Meanwhile, between 26.4 and 36 million people abuse opioids around the world.

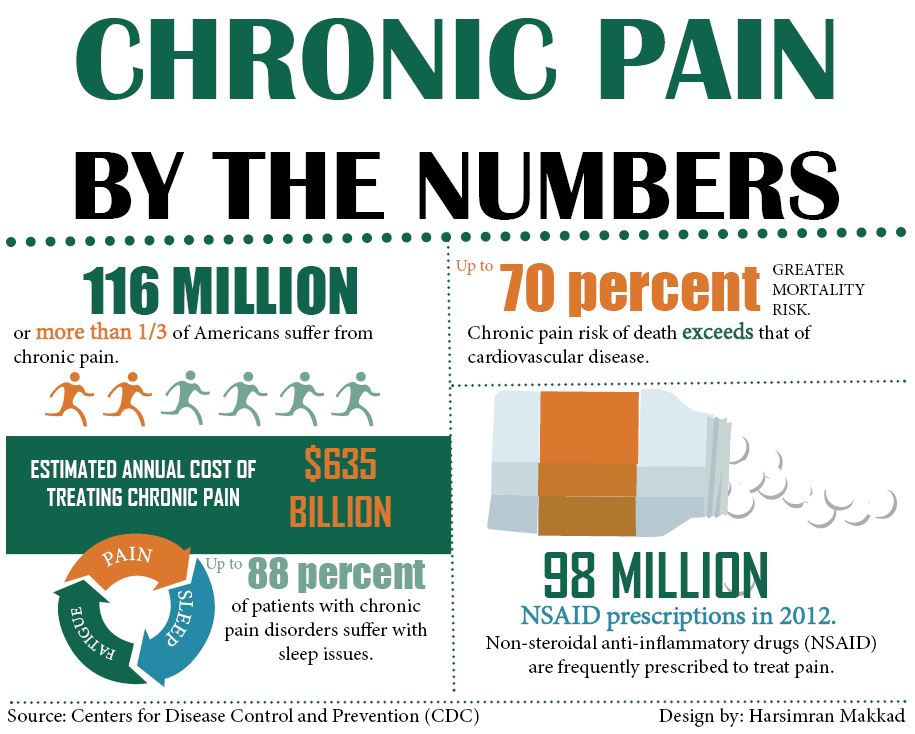

Furthermore, chronic pain is the primary cause of disability in the U.S., costing the country $635 billion each year.

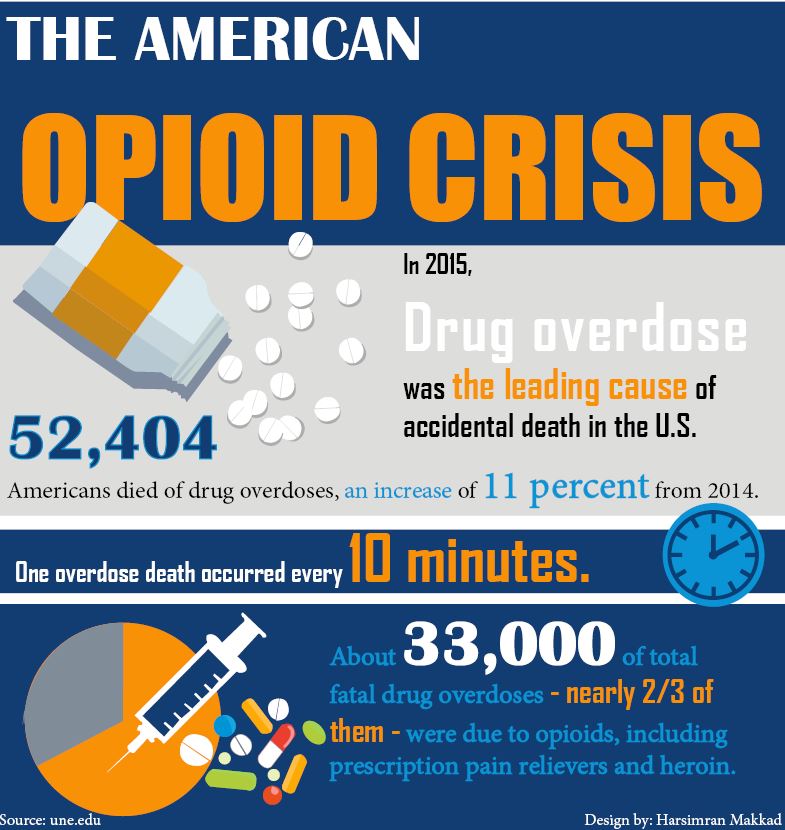

Yes, the original opioid crisis, the one centering around addiction and overdose, is a major issue that plagues the U.S., particularly the Cincinnati and northeastern Kentucky area.

And undoubtedly, increased prescription of opioids has contributed to this epidemic.

But there is an important distinction between using medicine for a health condition and misusing it that must be recognized, not ignored.

Opioids provide patients undergoing surgery, suffering from traumatic injuries, or fighting cancer with the relief they need, allowing them to function during everyday life.

Furthermore, most people who take opioids for medicinal purposes do not abuse them. In fact, studies have found that the risk for addiction among these patients ranges from 0.07 to eight percent.

The fact is that when opioids are prescribed properly with screening and care, the risk of addiction decreases significantly.

This is the side we rarely hear: the beneficial impact of opioids on people with acute pain.

“I started keeping a list of pain patients who had committed suicide, unable to cope with the pain. Sometimes the list grows weekly, sometimes daily… My list has more than 100 entries. Children have lost mothers, fathers and grandparents. I have lost friends.

“Just a few years ago, discussion of suicide was rare in the community of pain patients. Now I see it on online bulletin boards, in article comments, and in online groups dedicated to the subject. That’s my opioid crisis,” Fuqua said.

There are different opioid crises in America that are going on now. While the crisis of those struggling with addiction deserves the time and attention of legislators and health-care providers, the crisis of people in pain do as well.