Your donation will support the student journalists of Sycamore High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

Faking humanity

Manipulating human genome holds potentially dangerous consequences

May 20, 2016

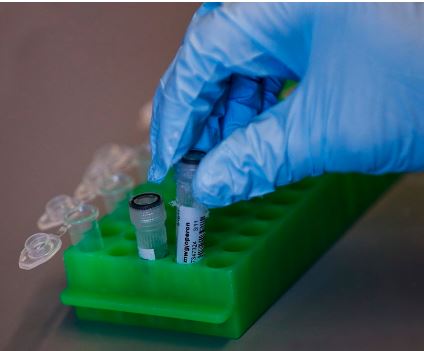

These test tubes of DNA are used for the gene editing of stem cells at the Lokey Stem Cell lab at Stanford University. With science and technology hurling at full speed, various moral and ethical concerns continue to arise about research and experimentation. Genetic engineering is an area of considerable debate about future consequences.

“How dangerous is the acquirement of knowledge and how much happier that man is who believes his native town to be the world, than he who aspires to be greater than his nature will allow.”

Romantic writer Mary Shelley’s sentiment in her novel Frankenstein, although against the science of her times, can still apply to the world today.

With such rapid advances and testing in the field of genetics, various concerns have arisen about the future of humanity. Human genomes are normally passed from parent to child, transferring inheritable traits through a natural process.

Yet scientists and researchers have begun to manipulate this natural process. How can this be allowed to continue when there are different consequences that can arise?

Developments in the area of genetic engineering suggest that someday, scientists will be able to artificially synthesize the human genome. And with the ability to build genomes becoming easier and cheaper, this day may be in the not-so-distant future.

But is this going too far?

Take, for instance, engineering the perfect baby. Scientists have discovered how to use a genome editing tool known as CRISPR with the hopes of eliminating inherited diseases in the decades to come.

But this also could provide a venue for parents to design the child they wish to have – picking eye color, features, and eventually intelligence.

Geneticist George Church of Harvard University, who helped discover CRISPR, claims that the intention is not to improve the human species in that way. But it is ultimately what he suggests: enhancements in the form of protective genes.

Jennifer Doudna, a biologist at the University of California, Berkeley, told The MIT Technology Review, “It cuts to the core of who we are as people, and it makes you ask if humans should be exercising that kind of power.”

Genetic engineering would encourage the spread of traits considered “superior.” And what happened the last time a group of people (really the work of one specific person) stressed so-called superior traits? The Holocaust.

No, it may not be that bad, but genetic engineering has the potential to produce a new “race” of humans with traits considered superior.

At the very least, there may be one group left behind – the humans of today or the humans “created” by altering their genetic sequencing.

In fact, the American Medical Association (AMA) holds that this germ-line engineering should not be done because it “affects the welfare of future generations” and could cause “unpredictable and irreversible results.”

Results such as unintended personal, social, and cultural consequences. The whole idea of manipulating the genome to attain certain traits could, in the end, redefine what it means to be “normal.”

And what about the risk of creating new diseases – ones with no treatment?

Research in this field as well as the testing should be limited both nationally and internationally. There should be restrictions on what can and cannot be done.

Now is the time to pull the breaks and prevent the potentially disastrous consequences that can occur in the distant future.